You know, I wrote Gladiator 2. Russell Crowe and Ridley Scott read the Proposition and asked me to write Gladiator, and I did write that. And luckily it was so completely unacceptable they didn’t even ask me to do rewrites. It wasn’t makeable. I wanted to write an anti-war film and use the gladiator as a raging war machine. It ended up in Vietnam and the Pentagon. He died in the first one so he comes back as the eternal warrior. It was just this really wacked out script. — Nick Cave to this writer, 2006

I was wanting to show the way history repeats itself, really and so in some ways it doesn’t matter what time it was, because this endless cycle goes on and on and on. — Polly Harvey to NME’s Emily Mackay, 2011

The first time I heard an advance copy of PJ Harvey’s extraordinary new album Let England Shake last December I knew I loved it but I didn’t really understand it. It looks like a message album but the message is occluded and I’ve been puzzling it over ever since. There is so much meaning to unpack and untangle, and even the simplest claims you could make (“It’s about England”; “Its about war”) are problematic. This is the record you get when a very clever, conscientious songwriter sweats to find a new way to deal with very old material.

War songs are about as old as war itself, whether celebrating the righteousness of combat, mourning the cost or simply longing to return home safely. What more is there to say about it? It’s sometimes necessary; it’s always awful. Hence Let England Shake is an anti-war record only in the sense that any vivid description of conflict will be anti-war — it contains no pacifist truisms. Harvey has always been interested in primal urges and the violence that people do to each other; now it is on a political scale.

Harvey has described her role here as bearing witness. “I know there are war poets and war artists and I thought well, where are the war songwriters?” she told NME. But she isn’t observing war firsthand like those poets and artists, nor even (with a couple of exceptions) wars within her lifetime. She is turning to the existing vocabulary of war and creating a collage of different perspectives in a way that reminded me of something former poet laureate Andrew Motion said on Radio 4’s Start the Week on Monday:

I am very aware when I’m reading war poems written by people who haven’t directly had experience of fighting on the frontline that however good their intentions are… there is a danger that they may aggrandise themselves by associating with the subject if they leave it purely and simply in their words… And I thought that by interviewing soldiers, reading books in which soldiers give their witness, and accommodating in my own words some of their thoughts and words, then I might get around that difficulty.

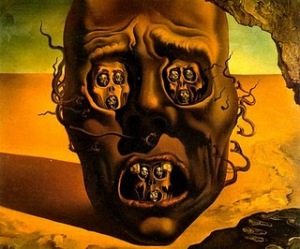

So I disagree with the New Yorker’s Sasha Frere Jones when he calls This Glorious Land “a thunderously obvious protest song”. The language is surely meant to sound blunt and ancient. As the album credits acknowledge, some of her lyrics (All and Everyone, The Colour of the Earth) were taken from the words of soldiers who fought at Gallipoli, others (The Glorious Land, In the Dark Places) from Russian folk songs, still others (The Words That Maketh Murder) from Goya’s brutal series of prints, The Disasters of War. Let England Shake is perhaps not so much about war as modes of representing war, and what they tell us about the endless, bloody cycle of history. The different voices cluster into a single combatant: what Nick Cave calls the eternal warrior and Buffy Sainte-Marie called the universal soldier.

The more you notice, and the more Harvey reveals in interviews, the more clues you find embedded in the record. She has already talked about finding inspiration in Harold Pinter and Jez Butterworth, Dali and Kubrick, the Doors and the Pogues, memoirs of the First World War and blogs from Iraq and Afghanistan, folk songs from Russia, Iraq, Cambodia and Vietnam. For example, the belly dancers in the opening line of Written on the Forehead are taken from New York Times reporter Anthony Shadid’s account of everyday life during the occupation of Iraq, Night Draws Near.

Her quotations and samples are often unusually intrusive — voices from the past poking through like restless spirits, reminders of what went wrong. (The first time I heard the jarring bugle call on This Glorious Land I thought I had another browser window open.) “All of the samples I used add meaning to the song, and the lyrics I’m singing,” says Harvey. It’s educational tracing them to the source. The voice snaking through England is from Said El Kurdi’s Kassem Miro, a Kurdish song recorded by the Gramophone and Typewriter Company (later EMI) on a talentspotting trip to the British Mandate of Mesopotamia just a few years before it became independent Iraq in 1932. The apocalyptic rasta chant on Written on the Forehead is Niney the Observer’s 1970 hit Blood and Fire, the first of many doom-laden releases as Jamaica plunged further into social and economic chaos.

The title track’s melody from the Four Lads’ 1953 novelty hit Istanbul (Not Constantinople) takes us back to the 1920s, when the Republic of Turkey, rising from the ashes of the defeated Ottoman Empire, insisted on its capital’s new official name. Hanging in the Wire quotes Vera Lynn’s Second World War comforter The White Cliffs of Dover (echoes of Harvey’s 2007 album White Chalk too). And as other critics have already observed, the sardonic quotation from Eddie Cochran’s Summertime Blues (“What if I take my problems to the United Nations?”) throws the reader back to the Cold War 1950s, then further (by association) to the League of Nations’ doomed attempts to broker world peace after the First World War, and then right back to the present day, when the beleaguered UN is no guarantee of peace nor protection.

All this internationalism at first made me think it was meaningless to call Let England Shake a record “about” England but then I realised that England (or rather the United Kingdom) is where all roads lead. Who granted independence to Iraq and Jamaica and ceded it to the USA? Who defeated the Ottoman Empire? Who was a founding member of both the League of Nations and the UN? Who invaded Iraq in 2003? The England that Harvey loves, a place of fog-wreathed mystery on White Chalk, is here a bloodied and bloodthirsty entity. It would not be what it was without the wars that it won and the wars that it lost. “I live and die through England,” she sings. “It leaves sadness/It leaves a taste/A bitter one.”

I think it’s a masterpiece — certainly the most persuasive and original album of political songwriting in many years — and I hardly want to listen to anything else. The mood is hazy and elusive, with simple melodies and a high register chosen (she has said) so as not to make the record overbearing and didactic. The sound is airy, though every song mentions some combination of greedy mud, clawing branches and deep waters, suggesting that war is not so much an offence against nature as a manifestation of it. The earth devours its dead. The universal soldier marches on.

Note: From the top, the pictures are: ANZAC troops during the battle of Chunuk Bair, Gallipoli August 1915; Goya’s Great Deeds! Against the Dead!, from his series The Disasters of War, inspired by the Peninsular War 1808-14; Dali’s The Face of War, inspired by the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939.

Note 2: One influence Harvey has cited is Abel Meeropol’s Strange Fruit (Bitter Branches recalls Meeropol’s original title Bitter Fruit), which I discuss in the first chapter of the book and in this excerpt in today’s Guardian.

18 Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Brilliant piece, thank you… I have been wondering about the lyrics of this album more than a while!

Thanks. It’s taken till now for me to understand exactly why the lyrics are so complicated.

“Who granted independence to Iraq and Jamaica and ceded it to the USA? Who defeated the Ottoman Empire? Who was a founding member of both the League of Nations and the UN? Who invaded Iraq in 2003?”

The United Kingdom? This may seem pedantic but it’s a pretty major point to your argument. You can’t just ignore the existence of the other members of the Union!

Not pedantic at all – just correct. I’ve inserted a clarification. Thanks!

I think it is an interesting point – is PJ Harvey engaging in the all-too-common and (in the non-England UK countries) much hated practice of using ‘England’ as a synonym for the UK? Craiglockhart in Edinburgh played a rather pivotal role in the development of the ‘war poets’, and Scotland/Wales have some famous war poets themselves (not too familiar with NI’s history in this area, I’m afraid). And of course, all countries of the UK lost people in the Great Wars (and continue to in Iraq, Afghanistan). If she deliberately chose ‘England’ as meaning only England, then I assume there is some specific reason for doing so.

I thought of it more that PJ, not unlike Billy Bragg, is into expressing and acknowledging her own ‘Englishness’. The UK and/or Great Britain are the administrations that rule but ‘England’ is the spiritual home of Harvey, Bragg and the folk tradition they have both been influenced by. ‘I’m not looking for a New England’ wouldn’t have sounded right as ‘I’m not looking for a New United Kingdom’. When soldiers fight they are still encouraged to fight for ‘King and country’ and PJ Harvey’s country of origin is England.

P.s. My favourite war correspondent album is Drums and Guns by Low. I have listened to Let England Shake a couple of times now, and though it sounds amazing it hasn’t toppled D and G from the top spot, yet. I think it is something to do with the pitch of the anger. Sparhawk let’s rip once or twice in such a visceral way but Polly J doesn’t here, even though we know she can.

Regarding tracing her samples back to their source, I was wondering what you made of the “elements” of The Police track The Bed’s Too Big Without You she uses in This Glorious Land….

Still on my first few listens but I am really enjoying this album – and I like your idea about the samples\quotes ‘poking’ through from different moments in time.

I also think the strangely catchy, upbeat quality of the tunes versus their rather more sombre, gruesome lyrics creates a really effective, unsettling, discordant mix. Makes me think of those jolly marching songs soldiers sing on their way to war.

Ha, I was taken back by the Police bit too. I guess she just liked the tune.

Agree with your “marching song” idea – All And Everyone is exactly that.

[…] stop listening/thinking about PJ Harvey’s Let England Shake. Thankfully, I’m not alone. Here’s a really fascinating, revealing piece on the album’s themes, creation, and influe… (among other places). You gotta click over to see the whole thing (it’s full of great images […]

where can I see the extra information you’re talking about?

What extra information?

Sorry to nitpick like the history nerd I am but when did England (or the UK) cede Iraq or Jamaica to the US? That never happened did it, at least not literally? I suppose it could be argued that Iraq and Jamaica have metaphorically been ceded to the US if you look at it like the US has become the new world imperial power like the British empire of old. Certainly plenty of Iraqis probably see the US like that but I don’t know what Jamaican’s would make of the idea of their being annexed by America.

Never the less I get your gist and agree that it evokes a lot of international-external themes but in doing so is still about England both its current war but also its past wars and how history can seem to repeat.

I must say considering the revolutions occurring in North Africa-Middle East some of these lyrics resonate all the more strongly. ‘Written on the forehead’ especially.

Hi Robbie. I’m afraid you’ve misread it. When I say ceded “it” I mean “independence” not “Jamaica and Iraq”. If I had written what you say then I would have to hang my head in shame. But thanks for being so tactful and understated about what seemed to you like a massive blunder.

Really enjoyed reading this piece, but it seems strange to me that there’s no attempt at relating the record to the impact that the wars of the last decade have had on ‘england’, where the soldiers today end up in prison or on the dole; where to the population, ‘England’ means either racist supremicism, or an embarrassing apology for Empire, or something they simply can’t relate to so they go and burn flags at military funerals. To me, that’s what this record speaks to, and in a very affecting and delicate way. I’m completely obsessed by it lately, like you, I can’t listen to anything else. But moreover I feel grateful that finally a musician has managed to engage with these questions, doubts, and traumas in such a powerful way.

I know this response is late but I wanted to thank you for laying open all the clues that I knew were there but couldn’t piece together. Your article on this album has helped piece together just how brilliant Ms. Harvey really is. Thank you again.

I take your point about the war, but I must admit that part of the record left me completely cold. Something about there being little left to say on that subject.

My ears pricked up when she started detailing her love/hate for England. It was refreshing to hear a singer talk about their feelings about this country.

I’d love to know what you thought about that bit, Dorian.

A little more research, in particular the book Strange Fruit by David Margolick. The song is about one body:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.